Animal That Looks Like Cat and Bear

| Binturong | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific nomenclature | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Course: | Mammalia |

| Lodge: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Viverridae |

| Subfamily: | Paradoxurinae |

| Genus: | Arctictis Temminck, 1824 |

| Species: | A. binturong [1] |

| Binomial proper name | |

| Arctictis binturong [1] (Raffles, 1822) | |

| |

| Binturong range | |

The binturong (Arctictis binturong) (, bin-TURE-ong, BIN-ture-ong ), also known as the bearcat, is a viverrid native to South and Southeast Asia. It is uncommon in much of its range, and has been assessed every bit Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List because of a declining population trend that is estimated at more than than thirty% since the mid 1980s. [2] The binturong is the merely living species in the genus Arctictis.

Taxonomy [ edit ]

Viverra binturong was the scientific name used by Thomas Stamford Raffles in 1822 for a binturong collected in Malacca. [iii] The scientific name of the genus Arctictis was coined past Coenraad Jacob Temminck in 1824. [4] Arctictis is a monotypic taxon; its morphology is similar to that of members of the genera Paradoxurus and Paguma . [five]

Etymology [ edit ]

The name Arctictis ways 'bear-weasel', from Greek arkt- 'bear' + iktis 'weasel'. [6] In Riau, Indonesia it is called 'benturong' and 'tenturun'. [7] Its mutual proper name in Borneo is "binturong", which is related to the Western Malayo-Polynesian root "ma-tuRun". [viii]

Characteristics [ edit ]

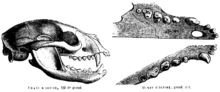

Skull and dentition of the binturong, as illustrated in Paul Gervais' Histoire naturelle des mammifères

The binturong is long and heavy, with curt, stout legs. It has a thick coat of coarse blackness hair. The bushy and prehensile tail is thick at the root, gradually tapering, and curls inward at the tip. The muzzle is curt and pointed, somewhat turned upwards at the nose, and is covered with bristly hairs, dark-brown at the points, which lengthen as they diverge, and form a peculiar radiated circumvolve circular the face. The eyes are large, black and prominent. The ears are brusk, rounded, edged with white, and terminated by tufts of black pilus. There are six brusque rounded incisors in each jaw, two canines, which are long and sharp, and vi molars on each side. The hair on the legs is brusk and of a yellowish tinge. The feet are five-toed, with big strong claws; the soles are bare, and applied to the ground throughout the whole of their length; the hind ones are longer than the fore ones. [3]

In general build the binturong is essentially like Paradoxurus and Paguma, but more than massive in the length of the tail, legs and feet, in the structure of the scent glands and larger size of the rhinarium, which is more convex with a median groove being much narrower higher up the philtrum. The contour hairs of the glaze are much longer and coarser, and the long hairs clothing the whole of the dorsum of the ears project beyond the tip equally a definite tuft. The anterior bursa flap of the ears is more widely and less deeply emarginate. The tail is more muscular, peculiarly at the base of operations, and in color generally similar the body, but commonly paler at the base of operations beneath. The body hairs are frequently partly whitish or buff, giving a speckled appearance to the pelage, sometimes and so pale that the whole body is mostly straw-coloured or grey, the young being frequently at all events paler than the adults, but the caput is always closely speckled with grayness or buff. The long mystacial vibrissae are clearly white, and at that place is a white rim on the summit of the otherwise black ear. The glandular expanse is whitish. [five]

The tail is well-nigh every bit long equally the head and body, which ranges from 71 to 84 cm (28 to 33 in); the tail is 66 to 69 cm (26 to 27 in) long. [ix] Some captive binturongs measured from 75 to 90 centimetres (thirty–35 in) in head and trunk with a tail of seventy cm (ii ft 4 in). [10] Mean weight of captive adult females is 21.9 kg (48 lb 4 oz) with a range from 11 to 32 kg (24 to 71 lb). Captive animals frequently counterbalance more than wild counterparts. [11] 12 captive female person binturongs were plant to counterbalance a mean of 24.4 kg (53 lb 13 oz) while 22 males weighed a mean of 19.3 kg (42 lb 9 oz). [12] The estimated mean weight of wild females per one study was ten.v kg (23 lb 2 oz). [xi] However, seven wild male person binturongs in Thailand were found to weigh a mean of 13.3 kg (29 lb v oz), while 1 female was of similar weight at thirteen.5 kg (29 lb 12 oz). [13] One estimate of the mean body mass of wild binturongs was 15 kg (33 lb). [14] The binturong appears to be the largest species of the viverrid family, rivaled only by the African civet, which weighs a mean of about 11.3 kg (24 lb 15 oz). [xv] [16] [17]

Both sexes take smell glands; females on either side of the vulva, and males between the scrotum and penis. [18] [19] The musk glands emit an odour reminiscent of popcorn or corn chips, probable due to the volatile compound 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline in the urine, which is besides produced in the Maillard reaction at loftier temperatures. [20] Dissimilar nearly other carnivorans, the male binturong does not have a baculum. [21]

Distribution and habitat [ edit ]

The binturong occurs from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia to Lao people's democratic republic, Kingdom of cambodia, Vietnam and Yunnan in Red china, and Sumatra, Kalimantan and Java in Indonesia to Palawan in the Philippines. [2] It is confined to tall wood. [22] In Assam, it is common in foothills and hills with skillful tree embrace, but less so in the forested plains. It has been recorded in Manas National Park, in Dulung and Kakoi Reserved Forests of the Lakhimpur district, in the loma forests of Karbi Anglong, North Cachar Hills, Cachar and Hailakandi Districts. [23] In Myanmar, binturongs were photographed on the ground in Tanintharyi Nature Reserve at an meridian of 60 m (200 ft), in the Hukaung Valley at elevations from 220–280 chiliad (720–920 ft), in the Rakhine Yoma Elephant Reserve at 580 m (1,900 ft) and at iii other sites up to 1,190 g (three,900 ft) top. [24] In Thailand's Khao Yai National Park, several individuals were observed feeding in a fig tree and on a vine. [25] In Laos, they have been observed in extensive evergreen forest. [26] In Malaysia, binturongs were recorded in secondary woods surrounding a palm estate that was logged in the 1970s. [27] In Palawan, it inhabits chief and secondary lowland forest, including grassland–wood mosaic from sea level to 400 m (1,300 ft). [28]

Taxonomy [ edit ]

Viverra binturong was the scientific name proposed by Thomas Stamford Raffles in 1822 for a specimen from Malacca. [three] The generic name Arctictis was proposed by Coenraad Jacob Temminck in 1824. [29] In the 19th and 20th centuries, the following zoological specimens were described: [30]

- Paradoxurus albifrons proposed by Frédéric Cuvier in 1822 was based on a drawing of a binturong from Bhutan prepared past Alfred Duvaucel. [31]

- Arctictis penicillata by Temminck in 1835 were specimens from Sumatra and Java. [32]

- Arctictis whitei proposed by Joel Asaph Allen in 1910 were skins of ii female binturongs nerveless in Palawan Island in the Philippines. [33]

- Arctictis pageli proposed past Ernst Schwarz in 1911 was a skin and skull of a female nerveless in northern Borneo. [34]

- Arctictis gairdneri proposed by Oldfield Thomas in 1916 was a skull of a male binturong collected in southwestern Thailand. [35]

- Arctictis niasensis proposed by Marcus Ward Lyon Jr. in 1916 was a binturong skin from Nias Isle. [36]

- A. b. kerkhoveni by Henri Jacob Victor Sody in 1936 was based on specimens from Bangka Island. [37]

- A. b. menglaensis by Wang and Li in 1987 was based on specimens from the Yunnan Province in China. [38]

Nine subspecies have been recognized forming two clades. The northern clade in mainland Asia is separated from the Sundaic clade by the Isthmus of Kra. [38]

Ecology and beliefs [ edit ]

Binturong photographed by a photographic camera trap at a feeding platform on a fruiting Ficus

The binturong is active during the day and at night. [25] [26] Iii sightings in Pakke Tiger Reserve were by day. [39] Thirteen camera trap photograph events in Myanmar involved one around dusk, seven in total night and 5 in wide daylight. All photographs were of unmarried animals, and all were taken on the footing. Every bit binturongs are not very nimble, they may have to descend to the ground relatively oft when moving between trees. [24]

5 radio-collared binturongs in the Phu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary exhibited an arrhythmic activity dominated by crepuscular and nocturnal tendencies with peaks in the early on morning and tardily evening. Reduced inactivity periods occurred from midday to late afternoon. They moved between 25 thou (82 ft) and 2,698 g (8,852 ft) daily in the dry season and increased their daily motion to 4,143 chiliad (13,593 ft) in the wet season. Ranges sizes of males varied between 0.9 and 6.1 km2 ( 3⁄8 and 2+ 3⁄eight sq mi). 2 males showed slightly larger ranges in the moisture season. Their ranges overlapped between thirty and 70%. [14] The average home range of a radio-collared female in the Khao Yai National Park was estimated at 4 kmii (1+ i⁄2 sq mi), and the one of a male person at iv.5 to 20.five km2 (1+ 3⁄four to 8 sq mi). [40]

The binturong is substantially arboreal. Pocock observed the behaviour of several captive individuals in the London Zoological Gardens. When resting they prevarication curled upwardly, with the caput tucked under the tail. They seldom leaped, simply climbed skillfully, albeit slowly, progressing with equal ease and confidence along the upper side of branches or, upside down, below them. The prehensile tail was always ready as a assistance. They descended the vertical bars of the muzzle head first, gripping them between their paws and using the prehensile tail equally a check. When irritated they growled fiercely. When on the cruise they periodically uttered a serial of depression grunts or a hissing sound made by expelling air through partially opened lips. [5]

The binturong uses its tail to communicate. [xviii] It moves about gently, often coming to a stop, and oft using the tail to keep balance, clinging to a branch. It shows a pronounced comfort behaviour associated with training the fur, shaking and licking the hair, and scratching. Shaking is the most characteristic element of comfort behaviour. [41]

The species is normally quite shy, only aggressive when harassed. It is reported to initially urinate or defecate on a threat and then, if teeth-baring and snarling does non deter the threat, it uses its powerful jaws and teeth in self-defense force. When threatened, the binturong will normally flee into a nearby tree, but as a defence force mechanism the binturong may sometimes balance on its tail and flash its claws to appear threatening to potential predators. Predation on developed binturong is reportedly quite rare by sympatric species like the leopard, clouded leopard and reticulated python. [42]

Diet [ edit ]

The binturong is omnivorous, feeding on minor mammals, birds, fish, earthworms, insects and fruits. [9] It also preys on rodents. [22] Fish and earthworms are probable unimportant items in its diet, as it is neither aquatic nor fossorial, coming beyond such casualty only when opportunities nowadays themselves. Since it does non take the attributes of a predatory mammal, most of the binturong's diet is probably of vegetable matter. [5] Figs are a major component of its diet. [25] [39] [43] Captive binturongs are particularly addicted of plantains, just also eat fowls' heads and eggs. [3]

The binturong is an important agent for seed dispersal, especially for those of the strangler fig, considering of its ability to scarify the seed's tough outer covering. [44]

In captivity, the binturong's diet includes commercially prepared meat mix, bananas, apples, oranges, canned peaches and mineral supplement. [11]

Reproduction [ edit ]

The boilerplate age of sexual maturation is thirty.four months for females and 27.7 months for males. The estrous wheel of the binturong lasts 18 to 187 days, with an boilerplate of 82.v days. Gestation lasts 84 to 99 days. Litter size in captivity varies from i to half-dozen immature, with an boilerplate of two immature per birth. Neonates counterbalance between 280 and 340 g (x and 12 oz), and are often referred to as shruggles.[ citation needed ] Fertility lasts until fifteen years of age. [eleven]

The maximum known lifespan in captivity is idea to exist over 25 years of historic period. [45]

Threats [ edit ]

Major threats to the binturong are habitat loss and deposition of forests through logging and conversion of forests to not-forest land-uses throughout the binturong's range. Habitat loss has been severe in the lowlands of the Sundaic function of its range, and there is no evidence that the binturong uses the plantations that are largely replacing natural wood. In China, rampant deforestation and opportunistic logging practices have fragmented suitable habitat or eliminated sites altogether. In the Philippines, it is captured for the wildlife trade, and in the south of its range it is also taken for homo consumption. In Laos, it is 1 of the virtually frequently displayed caged alive carnivores and skins are traded frequently in at to the lowest degree Vientiane. In parts of Laos, information technology is considered a delicacy and as well traded as a food particular to Vietnam. [2]

The Orang Asli of Malaysia has the tradition of keeping binturongs as pets. [46] [47]

Conservation [ edit ]

Bharat included the binturong in CITES Appendix III and in Schedule I of the Wild Life Protection Act 1973, and so that it has the highest level of protection. In China, information technology is listed as critically endangered. It is completely protected in Bangladesh, and partially in Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Licensed hunting of binturong is immune in Republic of indonesia, and it is not protected in Brunei. [ii]

World Binturong Day, an event dedicated to binturong awareness and conservation, takes place yearly every 2d Sat of May. [48]

In captivity [ edit ]

Binturongs are common in zoos, and captive individuals correspond a source of genetic diversity essential for long-term conservation. Their geographic origin is either usually unknown, or they are offspring of several generations of convict-bred animals. [38]

References [ edit ]

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Species Arctictis binturong". In Wilson, D. East.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins Academy Press. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0 . OCLC62265494.

- ^ a b c d e Willcox, D.H.A.; Chutipong, W.; Greyness, T.N.Due east.; Cheyne, S.; Semiadi, G.; Rahman, H.; Coudrat, C.N.Z.; Jennings, A.; Ghimirey, Y.; Ross, J.; Fredriksson, Yard.; Tilker, A. (2016). "Arctictis binturong". IUCN Carmine Listing of Threatened Species . 2016: east.T41690A45217088. doi: x.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41690A45217088.en . Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Raffles, T. S. (1822). "XVII. Descriptive Catalogue of a Zoological Drove, made on account of the Honourable E Republic of india Company, in the Island of Sumatra and its Vicinity, under the Management of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough, with additional Notices illustrative of the Natural History of those Countries". The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. XIII: 239–274.

- ^ Temminck, C. R. (1824). "Tableau Méthodique". Monographie des Mammifères. Paris, Amsterdam: G. Dufour et D'Ocagne, Maison de Commerce. p. XXI.

- ^ a b c d Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Genus Arctictis Temminck". The creature of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Vol.Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 431–439.

- ^ Scherren, H. (1902). "arc-tic-tis". The Encyclopædic Dictionary. London: Cassell and Visitor. p. 54.

- ^ Wilkinson, R.J. (1901). "tenturun". A Malay-English lexicon. Hongkong, Shanghai and Yokohama: Kelly & Walsh Limited. p. 192.

- ^ Smith, A.D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (two): 435–490. doi:x.1353/ol.2017.0021.

- ^ a b Blanford, Due west. T. (1888–91). "57. Arctictis binturong". The Beast of British Bharat, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 117–119.

- ^ Arivazhagan, C. & Thiyagesan, K. (2001). "Studies on the Binturongs (Arctictis binturong) in captivity at the Arignar Anna Zoological Park, Vandalur". Zoos' Print Journal. xvi (ane): 395–402. doi: 10.11609/JoTT.ZPJ.16.1.395-402 .

- ^ a b c d Wemmer, C.; J. Murtaugh (1981). "Copulatory Behavior and Reproduction in the Binturong, Arctictis binturong" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 62 (2): 342–352. doi: 10.2307/1380710 . JSTOR1380710.

- ^ Moresco, A., & Larsen, R. S. (2003). Medetomidine–ketamine–butorphanol anesthetic combinations in binturongs (Arctictis binturong). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 34(4), 346-351.

- ^ Grassman, Fifty. I.; Janecka, J. E.; Austin, Southward. C.; Tewes, M. E. & Silvy, Northward. J. (2006). "'Chemical immobilization of gratis-ranging dhole (Cuon alpinus), binturong (Arctictis binturong), and yellow-throated marten (Martes flavigula) in Thailand". European Periodical of Wildlife Research. 52 (4): 297–300. doi:ten.1007/s10344-006-0040-8. S2CID46658064.

- ^ a b Grassman, L. I. Jr.; Tewes, Grand. E.; Silvy, N. J. (2005). "Ranging, habitat employ and activeness patterns of binturong Arctictis binturong and xanthous-throated marten Martes flavigula in north-central Thailand" (PDF). Wildlife Biological science. 11 (1): 49–57. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2005)xi[49:RHUAAP]2.0.CO;two.

- ^ Roots, C. (2006). Nocturnal animals. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ White, Fifty.J.T. (1994) Biomass of pelting forest mammals in the Lope´ Reserve, Gabonese republic. J. Anim. Ecol. 63, 449–512.

- ^ Hunter, L. (2022). Carnivores of the world (Vol. 117). Princeton University Press.

- ^ a b Story, H. E. (1945). "The External Ballocks and Perfume Gland in Arctictis binturong". Periodical of Mammalogy. 26 (1): 64–66. doi:ten.2307/1375032. JSTOR1375032.

- ^ Kleiman, D. Thousand. (1974). "Smell mark in the binturong, Arctictis binturong" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 55 (1): 224–227. doi:ten.2307/1379278. JSTOR1379278.

- ^ Greene, L. Chiliad.; Wallen, T. Due west.; Moresco, A.; Goodwin, T. E. & Drea, C. Thousand. (2016). "Reproductive endocrine patterns and volatile urinary compounds of Arctictis binturong: discovering why bearcats odour like popcorn". The Scientific discipline of Nature. 103 (5–6): 37. Bibcode:2016SciNa.103...37G. doi:10.1007/s00114-016-1361-4. PMID27056047. S2CID16439829.

- ^ Schultz, Nicholas One thousand.; Lough-Stevens, Michael; Abreu, Eric; Orr, Teri; Dean, Matthew D. (2016-06-01). "The Baculum was Gained and Lost Multiple Times during Mammalian Evolution". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (4): 644–56. doi:ten.1093/icb/icw034. ISSN1540-7063. PMC 6080509 . PMID27252214.

- ^ a b Lekalul, B.; McNeely, J. A. (1977). Mammals of Thailand. Bangkok: Clan for the Conservation of Wild animals.

- ^ Choudhury, A. (1997). "The distribution and condition of small carnivores (mustelids, viverrids, and herpestids) in Assam, India" (PDF). Modest Carnivore Conservation. xvi: 25–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-29.

- ^ a b Than Zaw, Saw Htun, Saw Htoo Tta Po, Myint Maung, Lynam, A. J., Kyaw Thinn Latt and Duckworth, J. West. (2008). "Status and distribution of small carnivores in Myanmar" (PDF). Pocket-sized Carnivore Conservation (38): 2–28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Nettlebeck, A. R. (1997). "Sightings of Binturongs Arctictis binturong in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand" (PDF). Small Carnivore Conservation (16): 21–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-29.

- ^ a b Duckworth, J. W. (1997). "Small carnivores in Laos: a condition review with notes on environmental, behaviour and conservation" (PDF). Modest Carnivore Conservation (xvi): 1–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-29.

- ^ Azlan, J. Yard. (2003). "The diversity and conservation of mustelids, viverrids, and herpestids in a disturbed wood in Peninsular Malaysia" (PDF). Small-scale Carnivore Conservation (29): 8–nine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-29.

- ^ Rabor, D. Southward. (1986). Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Manila: Natural Resource Management Eye, Ministry of Natural Resources and University of the Philippines.

- ^ Temminck, C. J. (1824). "XVII Genre Arctictis". Monographies de mammalogie. Paris: Dufour & d'Ocagne. p. xxi.

- ^ Ellerman, J. R.; Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). "Genus Arctictis. Temminck, 1824". Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 (Second ed.). London: British Museum of Natural History. p. 290.

- ^ Cuvier, F. (1822). "Benturong". In Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, East.; Cuvier, F. (eds.). Histoire naturelle des mammifères : avec des figures originales, coloriées, dessinées d'aprèsdes animaux vivans. Vol. 5. Paris: A. Belin.

- ^ Temminck, C. J. (1835). "Arcticte Binturong – Arctictis binturong". Monographies de Mammalogie. Vol. Two. Paris, Leiden: Dufour, Van der Hoek. pp. 308–311.

- ^ Allen, J. A. (1910). "Mammals from Palawan Island, Philippine Islands" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 13–17.

- ^ Schwarz, E. (1911). "7 new Asiatic mammals with Note on the Viverra fasciata of Gmelin". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Phytology, and Geology. 8. 7 (37): 634–640. doi:ten.1080/00222931108692986.

- ^ Thomas, O. (1916). "A new Binturong from Siam". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 8. 17 (99): 270–271. doi:x.1080/00222931508693780.

- ^ Lyon, M. W., Jr. (1916). "Mammals collected by Dr. W. Fifty. Abbott on the chain of islands lying off the western coast of Sumatra, with descriptions of xx-viii new species and subspecies". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 52 (2188): 437–462. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.52-2188.437.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sody, H. J. Five. (1937). On the mammals of Banka. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ a b c Cosson, Fifty.; Grassman, L. L.; Zubaid, A.; Vellayan, S.; Tillier, A.; Veron, G. (2007). "Genetic diversity of captive binturongs (Arctictis binturong, Viverridae, Carnivora): implications for conservation" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 271 (four): 386–395. doi:ten.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00209.10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12.

- ^ a b Datta, A. (1999). Modest carnivores in two protected areas of Arunachal Pradesh. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Order 96: 399–404.

- ^ Austin, S. C. (2002). Ecology of sympatric carnivores in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. PhD thesis, Texas University.

- ^ Rozhnov, V. Five. (1994). Notes on the behaviour and ecology of the Binturong (Arctictis binturong) in Vietnam. Small Carnivore Conservation x Archived 2015-04-29 at the Wayback Machine: four–5.

- ^ Ismail, M. A. Hj. (??). Binturong Archived February 3, 2013, at the Wayback Car. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

- ^ Lambert, F. (1990). "Some notes on fig-eating past arboreal mammals in Malaysia". Primates. 31 (three): 453–458. doi:10.1007/BF02381118. S2CID2911086.

- ^ Colon, C. P. & Campos-Arceiz, A. (2013). "The bear upon of gut passage past Binturongs (Arctictis binturong) on seed germination" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology . 61 (ane): 417–421.

- ^ Macdonald, D.Due west. (2009). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ "Creature Feature: The Binturong | Redbrick Sci&Tech". Redbrick. 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2022-x-01 .

- ^ Abdullah, Mohd Tajuddin; Bartholomew, Candyrilla Vera; Mohammad, Aqilah (2022-05-01). Resource Utilise and Sustainability of Orang Asli: Indigenous Communities in Peninsular Malaysia . Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-64961-6 .

- ^ "événements". ABConservation . Retrieved 2022-05-10 .

External links [ edit ]

- "Bearcat". Zooborns. 2008.

- Bird, Thousand. (2005). "Binturong". Wildlife Waystation. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23.

- "L'association Arctictis Binturong Conservation". ABConservation.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Animal That Looks Like Cat and Bear

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binturong